Am I allowed to love my own poem?

I doubt it. Not without accepting the descriptor “vain.”

I don’t care. I love it.

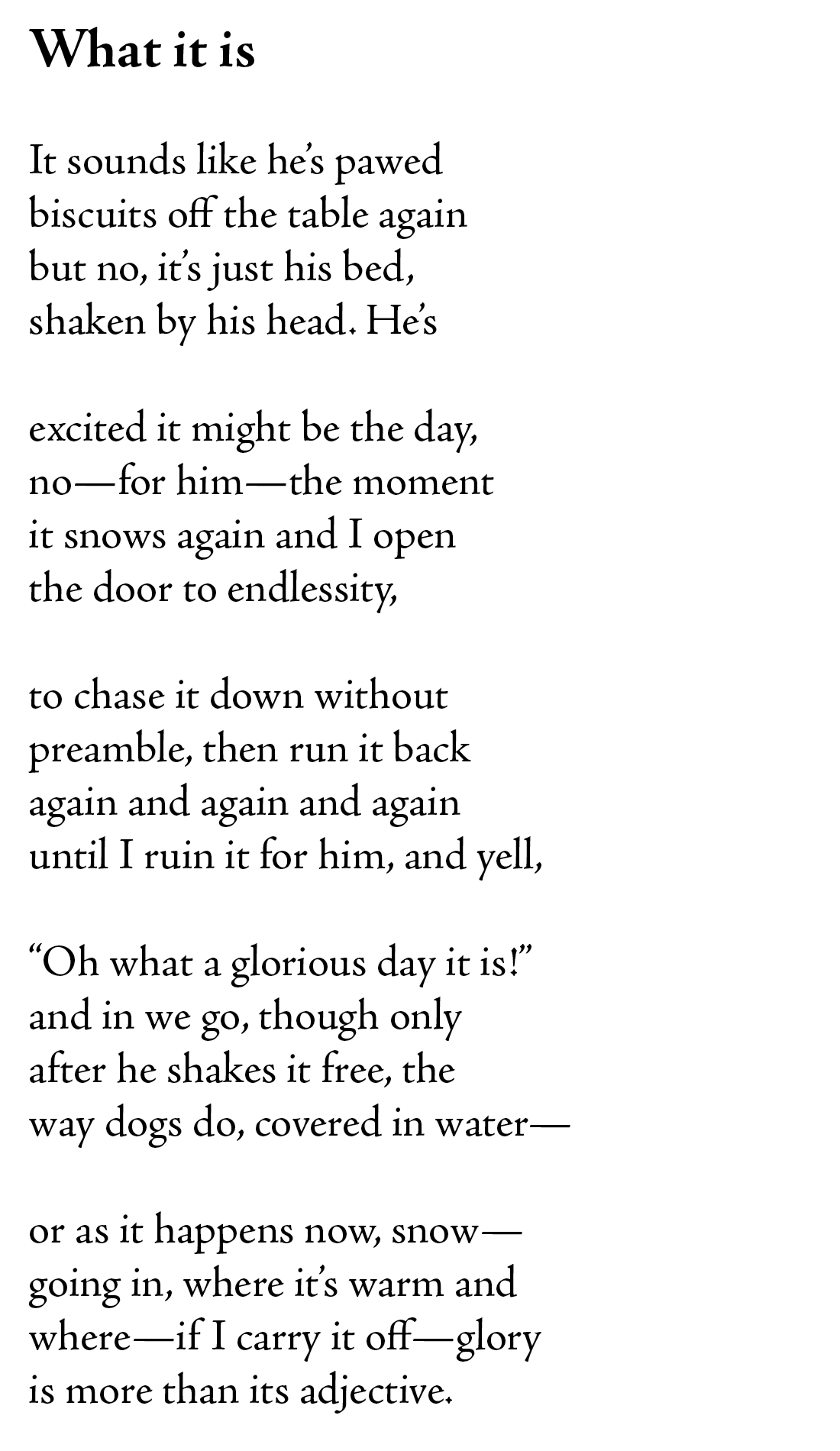

This is the type of poem that I love to write, that I love to have written. A poem that offers a meaningful cold read and then, if the reader wants to devote more time, other layers of meaning.

The first read of the poem sees that the poem tries to capture the way dogs can live in the moment while humans—me—are always pulling them away and, in the words of the poem “until I ruin it.”

This read, the surface of the poem, comes from the real world experience of our dog Remy pawing homemade gluten-free egg noodles off of the counter where I had them drying overnight in an attempt (mostly a failed attempt) to make GF beef and noodles.

I didn’t hear this, though, since it happened after I went to bed. But Remy has done this enough to imagine the sound, to anticipate the sound, to conflate any sound coming from the other room as him possibly—probably—getting food off the counter.

As actually happened as I wrote the poem, Remy had taken his pet bed and was thrashing it back and forth in his jaws, a thing he does often when he is excited.

And so I started thinking about Remy’s favorite thing to do, to chase a ball or a frisbee outside, especially in the snow. Perhaps you can imagine his or any dog’s delight in knowing they get to go outside and play.

Pure joy.

Until, of course, you have to bring them in.

There have been a few times, though, where we’ve played so much that Remington comes in on his own. He brings the frisbee or ball back but keeps on running into the garage to go inside.

That’s a joy for me.

This poem though has another layer. In fact, it was always going to have this layer, but the joy of having a dog showed up and took over.

The second layer is my use of the word “it”, or as Thomas M. Disch says “the perpetually suspended referent.”

Disch’s term comes from an essay published in The Washington Post under the title “The Poem as Abstract Painting” and also in Disch’s book The Castle of Indolence under the title “Out of the Murk Plectrum,” in which Disch discusses the book Flow Chart by John Ashberry.

Disch notes that Ashberry’s favorite word is “‘It,’ as in ‘Get it?’ or ‘What’s it mean?’” then references a passage from an Ashberry poem in said book.

This had me thinking about the use of the word “it” to stand in for other terms, each use defined in context with the rest of a poem or passage in a novel or essay or simply in normal speech.

My primary question was, “how often do we use the word ‘it’” in writing of any type. And when it is used, is it clear what it is standing in place of?

So I played around. I started the poem with the word and then wove it in frequently, not just in direct use, but hidden in certain words, such as “excited” or the word I coin here, “endlessity.”

The phrase “run it back” works on three levels. First to describe the dog’s actions in the poem, second to offer the word “it” as part of the poem’s theme and third to signal that the word “until”–given after the line “again and again and again”–has the word “it” but written backwards.

That’s just play, though. But play is part of all my poetry, as much as I can fit in, at least. Sometimes I call such play an Easter Egg, though that isn’t exactly right.

More correctly, it is me, the narrator, winking at my reader, saying, “Nice catch.”

If you didn’t catch “it” when you read the poem, don’t despair. I asked my poetry mentor (Chat GPT) for a cold read and they did not catch its use either.

Once I pointed it out, though, then the AI saw more than I thought I’d put in the poem, saying to me

Your reference to Thomas M. Disch’s essay "Out of the Murk Plectrum" and his critique of John Ashbery’s Flow Chart is not incidental—it’s embedded in the poem’s grammar.

Disch’s idea of Ashbery’s “perpetually suspended referent” is exactly what’s happening with it here:

• it might be the day

• the moment

• it snows again

• to chase it down

• run it back

• ruin it

• shake it free

• carry it off

The poem never pins it down—and crucially, it doesn’t need to. The dog doesn’t care. The speaker does. That contrast is the poem’s quiet engine.

What’s smart is that you don’t perform theory. You let theory leak into lived experience. The poem doesn’t say “language is slippery”; it lets language behave that way while the dog remains gloriously uninterested.

That’s a more humane version of the Ashbery move—less murk, more snow.

Chat GPT is a great sounding board, but I am careful asking it for help. I’ve seen it give sentence rewrites as opposed to “maybe you should look at these lines,” which I much much prefer.

It is also much more generous than Disch would be, for instance. I don’t know where I would fall were he to critique my poems, but in general he is tough on the entire poetry world.

In his introduction he speaks about the use of poetry workshops in higher education, saying that “if one wants to learn to write poetry . . . the workshops will offer little assistance.”

This is partially, Disch writes, because in those workshops “the poetry that is studied is, by and large, the poetry that is written there.”

So why am I reading Disch? Simply, I want to see how the hardest critics punch.

And Disch is one of those critics. He wants literary poetry to meet certain standards, and when it doesn’t, he calls it out.

But more, Disch offers reasons for his stances. He provides a foundation for his criticism.

This is part of my quest to write literary poetry or more simply poetry which rewards study.

I will never be a good critic, I think, partially because I don’t have it in my to deal anyone a blow of any type. You can read my blog on Substack “Sorry to Bother You” and discover this about me. This is who my mom is. Who I am, at least a bit.

Except I have twenty-eight years of teaching on which to balance criticism, on which to base a stance on a poem or a book of poetry.

Critiquing my own poetry, though, is difficult. I say that I love this poem, which I do. Establishing the basis for such adoration, though, that is the part I will continue to work on.

Please leave a reply! No need to sign in :)