I’m in the kitchen typing and I can hear a chainsaw running outside, its buzzing staccato cutting through the crisp fall weather as well as whatever wood is being cut.

Our dog Remy notices it too. He’s sitting in front of the sliding door that leads out towards the sound. Remy patrols the doors and windows of the house, watching, listening.

And smelling. He often tucks his nose right up to the poor seal on the sliding back door and draws the outside in, breathing deeply and expressively. It’s a wonder to hear and watch.

The smell of cut wood always gut punches me with joy. A bad day, a sad day, a moment of anxiety, sunk in a memory or floating above flu symptoms, times when I just don’t want to feel good and have forgotten there is good to feel, there’s wood.

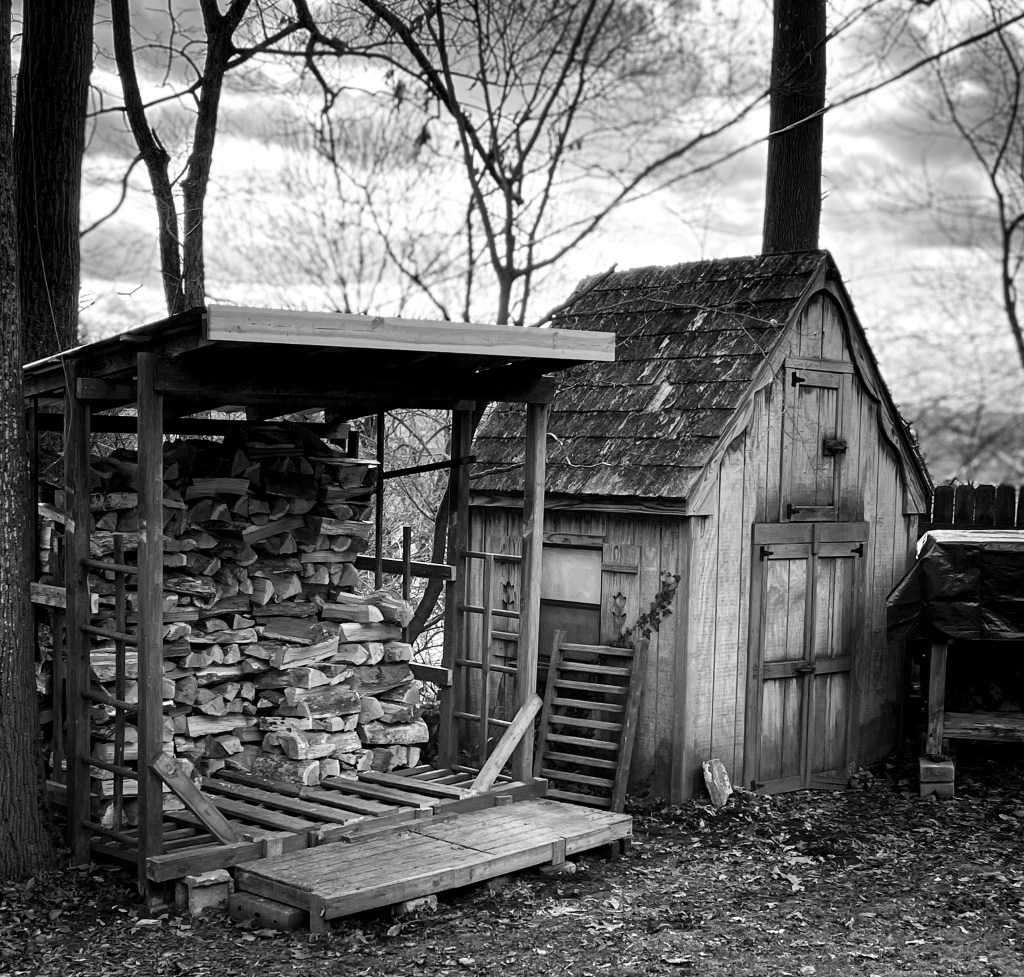

My son Oliver and I built a wood shed this past winter. I collected the random deck boards and two by fours and deck railing and the ladders and balcony I dismantled from the playhouse that will someday be my writer’s nook and built a woodshed. Somehow I found just enough to avoid buying any other wood.

Working without any plan other than a rectangular shape in my head, the lumber I found directed the build. The playhouse ladders became the front corner posts. Salvaged deck railing became the floor. Concrete blocks from an old outbuilding foundation now covered with ivy became the footers.

Oliver helped me with the corrugated roofing, the only part of the shed that wasn’t reclaimed. We screwed the metal down as the sun set, fairly sure of our success as the light ran out.

I had firewood delivered that week, a source I found through social media. Steve arrived with a cord of seasoned oak, helping me stack it in the new woodshed. He was a teacher as well, and we talked about his sabbatical and I explained how teacher retirement might work, even if you were only in your fifties.

Stacking wood delivers that glorious smell as sure as fresh cut grass, though the woodpile continues to pour out joy all year round, cut grass quickly turning into compost, its smell sent off in whatever wind blows in.

That first woodpile cord is now gone, burned, gasses released, the smell converted into other forms, the energy gone from chemical bonds to heat to light to molecular motion inside the bricks lining the fireplace, from there into the residual heat of the atmosphere, and much as the smell of cut grass, wind-dispersed, now just a memory.

I’ve found that Remy will reliably drop his frisbee for me if I stand on the small deck in front of the woodshed. At other times he is wary, playing a game perhaps, but probably just wanting to make sure the game of catch never ends.

So, when he stands ten feet away from me and refuses to offer me the frisbee, I’ll walk the forty feet to the backyard and stand on that platform. Sure enough, he’ll sprint past me as I walk, circling the small yard, dropping the disc on the corner of the deck and backing up cautiously. My throws from there are poor, sometimes heading off into the woods and possibly lost in trees, other times hitting the side of the house or the gutter, and sometimes glancing off the backboard of the basketball hoop and careening into the yard with a thwack.

Sometimes, though, the toss soars straight, true, past tree branches wanting to slow it down, past the cable and phone wires that stretch across our driveway ten feet up, through clear air, far enough to make Remy sprint, short enough he can catch the disc right before the far woods on the other side of the lawn.

That perfection coupled with the smell of the wood, standing there next to the woodpile, a moment doesn’t get much better than those surprising throws and the promise and memories of warm fires the wood smell offers, our family gathered around the living room, the dogs on pet beds, books being read and text messages sent.

I’ve moved the woodpile around the yard over the twenty-five years we’ve lived here, usually in relation to the trees that fell and needed cutting, splitting, and stacking. I’ve gotten better at ensuring most of the wood makes it to the fireplace, though early on I left some touching the ground on the bottom of the pile, not realizing that it would rot well before I’d burn the pieces above.

Lately wasps have been hibernating in some of the wood, warming up when I bring the wood in from the cold, suddenly appearing in the house, drunk at first, then lethargically flying toward the windows wanting to get outside.

Wendy is deathly allergic to these little creatures, keeping an Epipen close at hand in the summer, spring and fall. In the winter though, these wasps catch us off guard.

I saw a black rat snake come out of my mother-in-law’s birdhouse once, bit by bit emerging, longer and longer and longer than should have ever fit inside. Snakes strike terror in me, well beyond their actual danger. Those sleepy wasps, on the other hand, could kill Wendy.

Life is full of such discrepancy, true dangers ignored, flashes and bangs and fangs and shadows instead getting all the attention.

Chainsaws though, they sound dangerous, look dangerous, feel dangerous in your hand, and are well known to cause injury in a myriad of ways, some of them bloody, some of them crushing, some of them skin burns or liquid gas in wounds or projectiles in eyes or damage to hearing.

Many years ago a hurricane brought heavy winds in from the east, catching our well-inland trees’ root systems unprotected, felling ten or so large trees in one quick hour.

A novice chainsaw operator at the time, and still, truth be told, I took to cutting up limbs with my Craftsman eighteen-inch-bar chainsaw. I wore safety glasses and hearing protection and prepared in all of the ways I knew to be safe.

Using a chainsaw has always put fear into me, so I was cautious and careful and mindful. At first.

My confidence growing faster than my fear of being maimed, I moved deeper into the brush. Trees had fallen on top of each other, and I climbed carefully into the limbs, cutting branches here and there.

As you can imagine, this was all a bad idea. I was off the ground, on wet branches, holding a machine that spawned its own series of horror movies.

Suddenly I found myself launched into the air, the chainsaw thrown ten feet away, falling backwards into the mess of branches. I landed into a fork of the branches, my arms over each limb to my side, leaning back as if in a Lazy-Boy recliner, the branch giving a bit as I landed so that there was almost no sensation of landing. I could not have found a more comfortable place to sit, save an actual recliner.

This is a bad story, as it might imply chainsaws are not killing machines. They are killing machines. They are as dangerous as any tool I own.

When I was seven my parents would take us to our uncle’s and aunt’s where they would play bridge upstairs while we watched tv in the basement. We took sleeping bags so that we could be carried out to the car at 1:00 am in three sacks, not even needing to be woken.

Sleeping bags can be dangerous too, it turns out. I pulled my bag over my head and began hopping around the basemen oncet, playing a game perhaps many children have played.

As I tripped over a pillow and started falling forward, I realized that my hands were trapped and I couldn’t catch myself. Instead, I landed on the concrete floor directly on the top of my forehead.

As with the chainsaw incident, so many bad things could have happened. Instead, I felt my skull hit the ground and a wave of energy passed through my head that felt a bit like a bell ringing. There was no pain. There was no blood. There was no explanation.

I’d like to think that there are lessons here, about taking risks, about not assessing situations and decision making and having common sense. I’m not sure these stories offer such lessons. That they are cautionary tales.

In the late winter of 2011 – 2012 our fourteen-year old Golden Retriever Waldo was so sick from cancer that he couldn’t get up off the ground on his own and I knew he was in incredible pain.

That ten-minute drive to the clinic was agony. I talked to Waldo the entire way, remembering together the runs we’d taken, the trips to Vermont and Maine, playing with our kids in the yard, memory upon memory crashing down on us. He lay in the back of the van listening and panting.

My father-in-law met me at the vet clinic, an act of love that held me on my feet. I talked to Waldo and rubbed his ears and neck through the end. An entire era of memories and joy washed through me.

There should have been a lesson there, caution about falling in love with another dog or cat or fish or salamander. My father passed away a week later and once again I knew the pain that love is always inching towards.

So there might have been a lesson here. Wendy and I agreed to not get another dog for at least a year, to think hard about such a decision, that van ride with Waldo and that moment we said goodbye to each other offering so much caution.

Yet here I sit, three dogs in the house, three more times to go through such loss, three more chances to remember how precious friendship and family are, things that the smell of cut wood and the sound of chainsaws and the warmth of a living room fire attach to, as the wasp buries into the wood, hibernating in the hopes of heat and resurrection.

Oliver and Tess called on Friday from Seattle, a facetime call from their car. On the screen a black dog the size of Waldo and Remy popped his head, his tongue hanging out, his first trip home to their apartment.

“He chose us!” they said, telling the story of first meeting him at the rescue shelter. They sent a video of him licking Olly’s face over and over, falling over himself with happiness as all dogs will do, as all of us might do could we express our feelings for our loved ones without our natural reservations, without the caution of so many lessons supporting our life-stories like concrete blocks and repurposed wood.

I felt for one millisecond reservation for them, before the joy of knowing what Oliver and Tess had accepted, the fate of years and years of being gut-punched with joy over and over again, even at the end, lessons that might be learned instead becoming hope, danger be damned, climbing on branches under tension and trusting whatever force watches over us and offers miraculous soft landings and our heads ringing like bells.

Please leave a reply! No need to sign in :)